Antoni Tàpies (pronounced TAH-pee-ess) once said, “My first works of 1945 already had something of the graffiti of the streets and a whole world of protest — repressed, clandestine, but full of life — a life which was also found on the walls of my country.”

Born in Barcelona, Tàpies came to prominence in the late 1940s with richly symbolic paintings strongly influenced by Surrealist painters like Miro and Klee, a style he abandoned by the mid-1950s as he turned to what became his signature work: the heavily built-up surfaces that were often scratched, pitted and gouged and incised with letters, numbers and signs.

Tàpies was one of Spain’s main exponents of abstract and avant-garde art in the second half of the 20th century. His father was a lawyer and Catalan nationalist who served briefly with the Republican government. At 17, Tapies suffered a near-fatal heart attack caused by tuberculosis. He spent two years as a convalescent in the mountains, reading widely and pursuing an interest in art that had already expressed itself when he was in his early teens. Before devoting himself to being an artist beginning from 1943, he studied law for three years.

“He was the most radically Catalan artist in his thinking, his expression and references and at the same time the most universal in his language and international projection,” Catalan regional president Artur Mas said.

After studying in Paris, where he met Pablo Picasso, a fellow Catalan, Tapies began exhibiting regularly and, after the Surrealist adventures of his “magic period,” he set about transforming himself into a painter who, as the critic Roland Penrose put it in his monograph “Tàpies” (1978), “a painter who was to create mysteries in matter itself.”

Tapies worked with many different materials and formats

“When I dip the copper plate in a bucket of nitric acid, then the acid is my knife.”

Barbara Catoir. Conversations with Antoni Tàpies. Barcelona: Edicions Polígrafa, 1988: 121

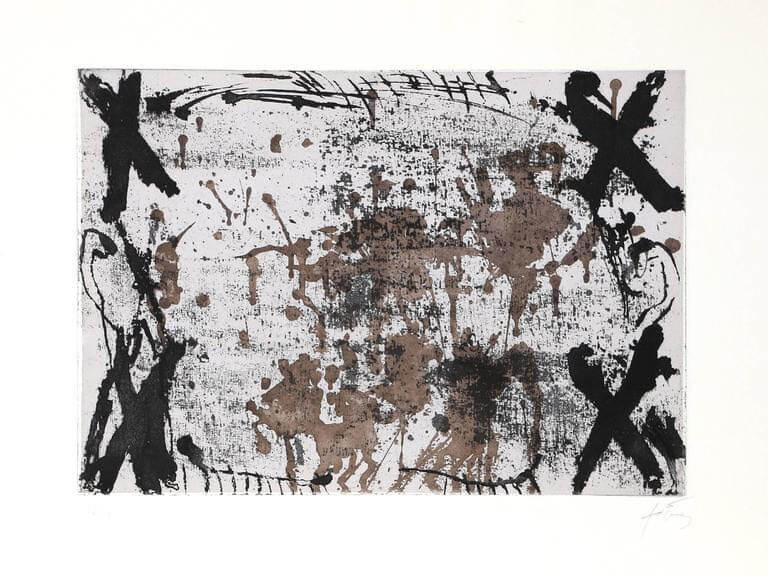

NU

Etching, aquatint in colors

31 3/8 x 42 1/2 in

79.6 x 108 cm

Overall: 41-3/4″h x 4’4-1/2″d

Edition 50

Signed “Tapies”

Framed nicely with the addition of museum glass

$6500.00

This aquatint/edition shows the experimentation of Antoni Tàpies in the field of engraving. Since the material aspects of the work of art are the central element of his work,

One of the challenges of this medium was to transfer the richness of textures that Tàpies achieved with his painting to the support, to the paper. This transfer was made through the copper plate, which Tàpies treated in the same way as a cardboard or a piece of paper: he did the same operations with his fingers, with the brushes. It was another way of scratching in which, as Tàpies said, the acid in which the plate was submerged replaced the knife.

The process of aquatint is similar to that of etching. Resin is spread in certain areas of the plate and heated. The resin adheres to it, creating tonal areas instead of lines. Contact of the acid dissolves the surface between the particles which is not covered by the resin, and creates a grainy feeling when stamped on the paper. Both etchings and aquatints and the series of engravings establish a common link of a plastic nature. Motifs such as the cross, the foot, the letter and others that are repeated in various forms do not have a narrative character, with a beginning, a development and an end, but of variations on a theme.

Below is the documentary Tàpies (1990), directed by Gregory Rood and produced by BBC – TVE Catalunya, which teaches the creative process of Antoni Tàpies in various formats (painting, engraving and ceramics), while shelling different events of his life and training.

ALSO AVAILABLE

La Clau del Foc 15

Lithograph

17 3/4 x 24 in

45 x 61 cm

$2500.00

Les Quatre Croix, 1969

Etching and aquatint in colors

height 17 1/4 in

height 43.8 cm

Edition 75

$ 2800.00