Jeweler PrintmakerFurniture Designer SculptorPhilosopher

Starting out as a painting student but soon being asked to reopen the metal workshop in 1939, Bertoia taught jewelry design and metal work. Later, as the war effort made metal a rare and very expensive commodity he began to focus his efforts on jewelry making, even designing and creating wedding rings for Ray Eames and Edmund Bacon‘s wife Ruth. When all the metal was taken up by war efforts, he became the graphics instructor. Still at Cranbrook, in 1943 he married Brigitta Valentiner, and then moved to California to work for Charles and Ray at the Molded Plywood Division of the Evans Product Company. Bertoia worked there until 1946, then sold his jewelry and monotypes until obtaining work with the Electronics Naval Lab in La Jolla. In 1950, he was invited to move to Pennsylvania to work with Hans and Florence Knoll. (Florence studied also at Cranbrook.) During this period he designed five wire pieces that became known as the Bertoia Collection for Knoll. Among these was the famous diamond chair, a fluid, sculptural form made from a welded lattice work of steel.

In Bertoia’s own words, “If you look at these chairs, they are mainly made of air, like sculpture. Space passes right through them.”

The chairs were produced with varying degrees of upholstery over their light grid-work, and they were handmade at first because a suitable mass production process could not be found. Unfortunately, the chair edge utilized two thin wires welded on either side of the mesh seat. This design had been granted a patent to the Eames for the wire chair produced by Herman Miller. Herman Miller eventually won and Bertoia & Knoll redesigned the seat edge, using a thicker, single wire, and grinding down the edge of the seat wires at a smooth angle—the same way the chairs are produced today. Nonetheless, the commercial success enjoyed by Bertoia’s diamond chair was immediate. It was only in 2005 that Bertoia’s asymmetrical chaise longue was introduced at the Milan Furniture Fair and sold out immediately.

https://harrybertoia.org/

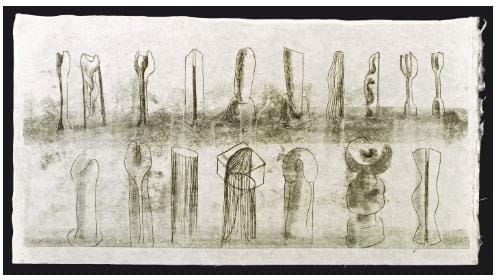

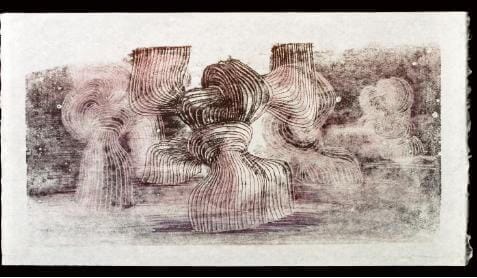

The MonoTypes

Bertoia developed his own style of creating monographics at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, and never worked with, or even met, other printmakers.

He would ink up a glass surface, place rice paper on the glass, and then create designs with fingers or hand tools from the backside of the paper. Each “print” is unique – never reproductions of another – and there are thousands of them. When Bertoia, looking for critique and direction, sent about 100 monotypes to Hilla Rebay at the Guggenheim Museum of Non-Objective Art in 1943, he was quite shocked when she asked to purchase the entire stock. He was up half the night determining a fee, and finally set $1000 as his compensation. When the subsequent Guggenheim show included many of his prints, Bertoia’s name gained recognition.

Bertoia loved the quickness and spontaneity of the medium of his graphics. While sculptures took weeks or months to produce, monotypes came to life in mere minutes. The series of 50 monotypes reproduced in the Harry Bertoia Fifty Drawings book “came into being in about twenty-four hours of uninterrupted work.” Most, if not all, of Bertoia’s designs, whether they are chairs or sculptures or tonals, were born on paper first. He started the monotypes in 1939 and continued throughout his life.

Untitled (#398), c. 1940s, 1940s

Monotype and collage on rice paper

Framed: 24 ½ x 30 ¾ inches

Image: 19 x 26 ¼ inches

$ 7500.00

Untitled (#52a), UNK

Monotype on rice paper 39 x 12 inches

Framed: 43.5 x 17.5 inches

$ 6500.00

Monotype on rice paper, UNK

Monotype on rice paper13 x 24 inches

Framed 17.5 x 29.5 inches

$ 6000.00

Untitled (#398), , c. 1960s

Monotype and collage on rice paper

19 x 26.25 inches

Framed: 25 x 30.75 inches

$ 6000.00

Untitled (#92), , c. 1950s

Monotype on rice paper13 x 24 inches

Framed: 17 x 28 inches

$ 5500.00