Renowned for his mixed-media works, Robert Rauschenberg was a painter and graphic artist whose works are often associated with the Neo-Dada movement; innovative with his technique and inspired by his fascination with what art truly encompasses, one of Rauschenberg’s most notable works is his Erased de Kooning Drawing that depicts exactly what the title suggests – the artist requested a drawing from De Kooning which he then erased over the course of two months, leaving only faint outlines of the original work. Rauschenberg’s ‘Combines’ came to define his career; using various mundane objects such as cardboard and even trash, combined with paint, the artist created his three-dimensional collage paintings of which he remarked ‘I think a picture is more like the real world when it is made out of the real world’ – such works as Rhyme and Bantam are among his most acclaimed Combines. (Artist website)

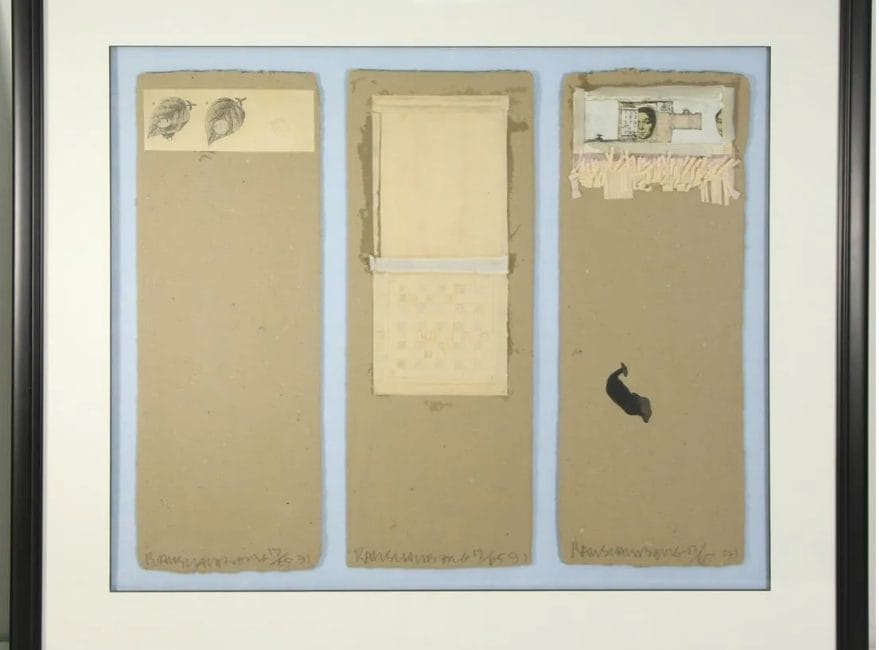

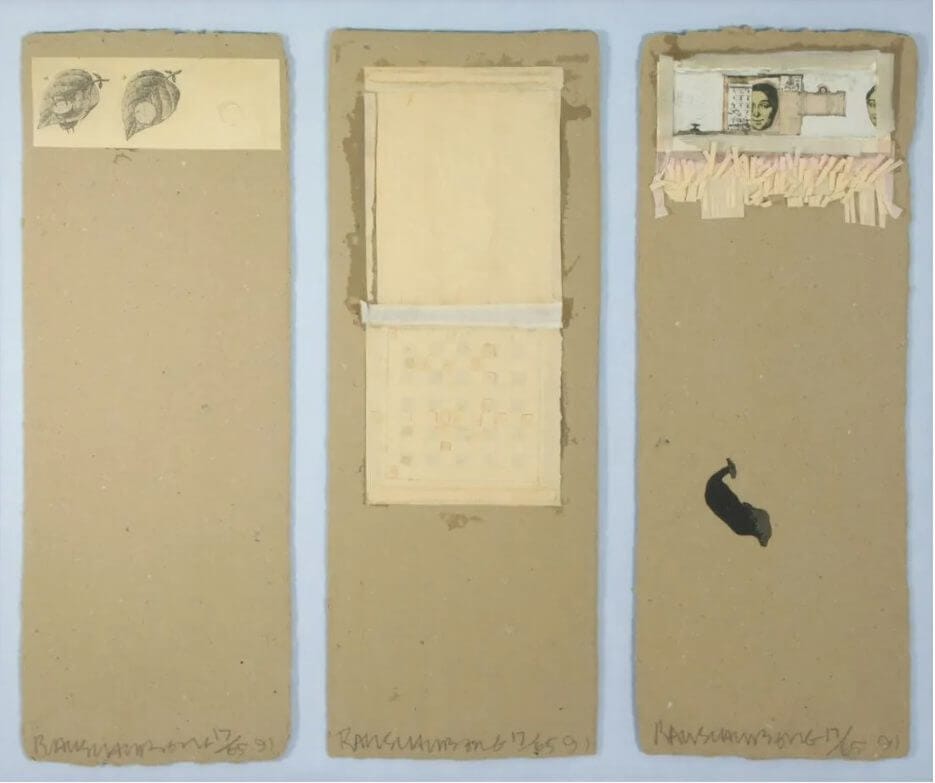

3 Shirtboards (from Shirtboards, Morocco, Italy ’52 Portfolio), 1991

Lithograph and Collage

39.3 x 28 cm variable

edition 65

$ 5,000.00

In 1953, Robert Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly went to Italy on an artist grant. Actually, the grant was for Twombly alone, but the meager sum kept them alive and working for a few months abroad. The money did, as money does, grow short, and Rauschenberg discovered he was broke and without a job. Hearing of an opportunity in Morocco, he spent his “return home” money to get there and Twombly joined him. Eventually hired by heavy equipment company, Rauschenberg made it home to the States.

Rauschenberg had next to nothing to buy art materials with, so he collaged cheap prints, newspaper, feathers, drawings, and random stuff onto the shirtboards from their laundry in an irreverent twist of his teacher Josef Albers’ technique. Bob would glue etchings and illustrations he found or bought in street stalls onto the leftover cardboards folded inside his laundered shirts. Many of these works were shown in Walter Hopps’ landmark Rauschenberg: The Early Fifties show at the Menil collection in Houston in 1991. Rauschenberg used his European experience to make a series of Joseph Cornell-like shadow boxes, though he had not yet heard of Cornell. He took a number of impressive photographs of Moroccan cities and landscapes, showing the influence of Aaron Siskind at Black Mountain College in Asheville, North Carolina. He also made a suite of these bizarre shirtboard collages, a strange hybrid of Surrealism and the unlikely influence of Joseph Albers.

In his Shirtboards, Rauschenberg cut from newspapers and books, setting a precedent that he continued throughout his life, but unlike his later work, the clippings do not seem formal experiments as much as static grounds, placed right in the center of the paper. Rauschenberg was famously frustrated with Albers discipline and his rigorous formal exercises. Albers would do the same in his prints and his Homage to the Square series, but would use an applied color theory to activate the static field. Rauschenberg’s Shirtboards are noticeably drab in terms of color, but he does activate the field. Adding insult upon insult, playfully of course, to Albers, he places pictures of birds and insects, feathers stuck in paper pockets, drawn arrows, and scientific diagrams into the formal exercise. Unwanted things, stuff of the world, floods into Alber’s sacred formal space.

The works give us a picture of an artist who was energetically exploring multiple possibilities and highlight the artist’s eagerness to experiment with whatever materials are available and of interest to him. They are unassuming, sober works, but contain many of the issues that Rauschenberg carried with him through his entire career. and beyond the Abstract Expressionism that was still hogging the art world limelight. If anything, the Shirtboards are a playful ribbing of Albers. In Morocco and North Africa, Rauschenberg took on these activities, turning them into vehicles for the hodge podge of life.

To fully understand Rauschenberg you must be aware Rauschenberg had no sense of color or of composition either. The eye jumps from place to place with what the critic Andrew Forge called “a lark like mobility.” But Rauschenberg didn’t seem to care about composition or color. He wasn’t after beauty. His is a democratic canvas where everything is equal, every color, every material (newspaper, political poster, fabric, an old shirt, a sock, a paint tube, scrap metal, taxidermy), every type of image (drawings by Cy Twombly and by his son Christopher, comic strips, prints of famous artworks, postcards of buildings and cows and presidents, Judy Garland’s autograph). This pursuit of radical egalitarianism—unwilling to privilege one thing over another, uninterested in hierarchies—started when Rauschenberg was studying at Black Mountain with Josef Albers

This is what Rauschenberg is famous for. As Leo Steinberg said, “He let life in.” Unlike Twombly, Rauschenberg doesn’t seem remotely interested in Abstract Expressionism at this time. On the surface, he seems more in line with someone like Max Ernst or even Tristan Tzara, using seemingly random things to create visual and verbal impact.

Unlike the Surrealists, Rauschenberg’s Shirtboards have a sort of crafty animism about them, a mixture between a voodoo fetish box and a handmade birthday card. They match the tone of the sculptures Rauschenberg was making at this time. Evidenced only by photographs, the sculptures appear much closer to Native American dream catchers than they do to anything going on in the French circles of Paris and New York. The sculptures were hairy, feathery mobiles shifting and swaying in the wind. The Shirtboards continue the spirit of these sculptures.

How fascinating to think about — Twombly furiously sketching, taking on the bravura gestures of Ab Ex with gesture itself, and Rauschenberg seemingly poking around the Moroccan terrain for rocks and feathers to make mobiles. Furthermore, Rauschenberg remade this work in 1990 published by Syria Studios, and early photographs of his New York studio shows the Shirtboards still hung with prominence on his proverbial mantle. What is it about these works that Rauschenberg does want to let go or what is it about them that Rauschenberg must carry with him?